I just finished watching All the President’s Men for the umpteenth time and still found it thrilling. I clapped at the end when they cut to that closeup of the automatic typing of the headlines that followed in the wake of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s investigative reporting. As the TV news coverage of Nixon’s 1973 inauguration plays in the background, all the politicos Woodward and Bernstein pursue in the movie, one after another, are convicted until, at last, Nixon resigns.

I was a kid when that happened in real life, a kid living in the suburbs of Washington DC and barely old enough to be watching Nixon’s resignation speech on a neighbor’s TV as I babysat their kids. It made an impression. By the time the film was released, I was reporting for my high school newspaper, by my senior year, features editor.

As a journalism major at the University of Maryland, I spent a lot of time in DC so the settings in the movie ring an old bell – the Library of Congress, the Kennedy Center, even Watergate (they had a great bakery there). In my final year, I moved to a seedy room on the edge of Adams Morgan where I could more easily report on happenings in the city for the university newspaper while finishing my final credits doing independent study. For a while, I covered my meagre expenses by working as a waitress at a music club in Capital Hill. (I was obsessed with the New Wave – but that’s another story.)

There’s a scene in All the President’s Men where Woodward and Bernstein huddle in the Library of Congress tracking down leads. As the camera pans out for a birds-eye view of the desks lining the building’s dome, I let out a squeal of recognition. I spent hours huddled at one of those desks, digging through microfilm for my final paper on underground newspapers. I aced it and received my diploma in the mail. I was now a journalist with a journalism degree living in the nation’s capital.

Much as I loved that kind of digging, I never applied for an internship at the Post, although I had friends working there. Maybe that had something to do with scenes from this movie still playing in my head. I couldn’t see myself banging on doors and banging out daily news. I wanted to cover the arts for magazines.

As it turned out, the Post wasn’t all political reporters dashing through newsrooms and meeting sources in dark parking garages. There is a strong magazine element to any big daily and I ended up writing for several sections of the Post as a freelancer – the Sunday magazine, the Style and Travel sections.

Even so, the movie had a major impact on me. For one thing, it left me and a lot of my journo friends dazzled by the power of the press. The government may be corrupt, big business may be corrupt, but the First Amendment gave us a chance to call them out. No matter what obscure part of the socioeconomic strata you ended up reporting on, this held true. We were protected. It was important to dig for and uncover the truth, and tell it straight. I still believe that.

Nearly 50 years after Woodward and Bernstein broke their big story, it feels a lot like we’re right back there again – which is, I’m sure, why Amazon licensed the right to stream All the President’s Men. The Post and the New York Times have been revived once again by political scandal, their reporters competing for big stories, chasing corruption at the highest levels, this time being threatened directly by the POTUS on his own Twitter feed.

It’s also the era of #metoo. Just like we bring a new world view – and a new self view – every time we reread a classic book, so it is with movies.

Here’s what I noticed this go-round: what a story of white men! White men running the country, co-opting other white men to help them break all the rules, young hungry white men running around a newsroom “humping it” while older white men yuck it up around the editor’s table.

I never really noticed before that the movie is essentially a story of an old boys’ club bringing in a couple new recruits.

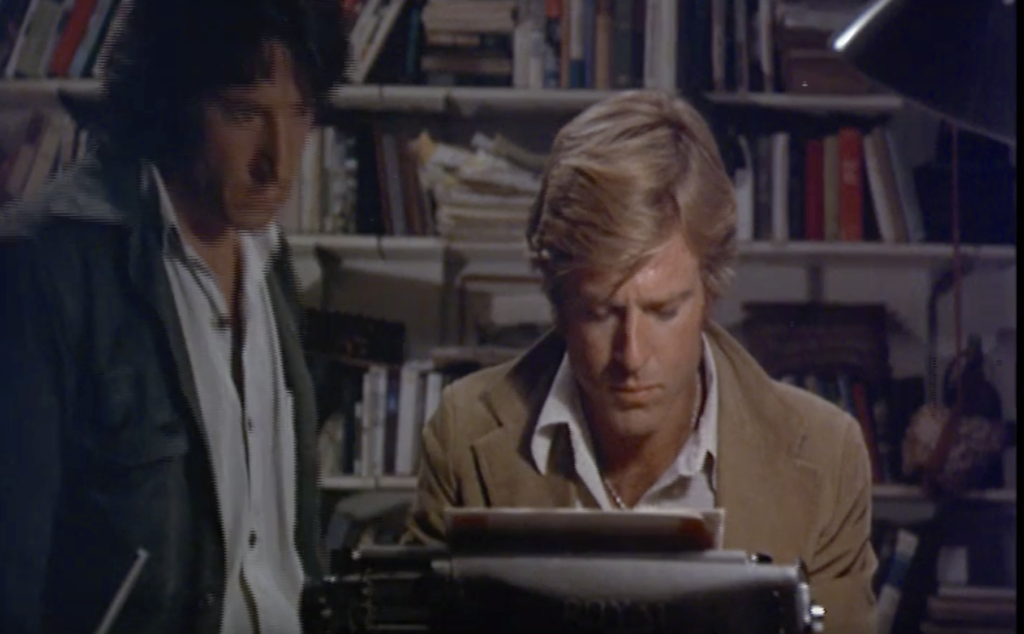

Woodard and Bernstein are often referred to as “the boys” by these old boys, at first suspiciously and then fondly. Redford and Hoffman don’t look much like boys in this movie. Redford was 39 when this film was made, playing a man who was 28. Dustin Hoffman was 38 playing 27.

And oh my lord, the fashions of the 1970s, especially in the newsroom. Redford somehow manages to look a little stodgy and Hoffman kinda hot, even though he comes up to Redford’s collarbone. This has a lot to do with the high-wasted ill-fitting camel-colored corduroy suit Redford wears. I never noticed this at the time. My dad had that suit in green. Hoffman wears dress shirts like Redford’s with the sleeves rolled up but Hoffman’s are form-fitting, tailor made, and he wears them with khakis. It’s a study of the power of fit and cut in men’s clothes. I also never noticed Hoffman’s big shiny shag haircut at the time. Hey, I knew guys with hair like that.

As for the women in this film…. There’s Sally, the reporter who helps “the boys” by repeating something Ken Clawson (former White House reporter and then married deputy director of White House communications) told her while having drinks in her apartment. In the film, Bernstein grabs Sally by the hand and drags her running through the newsroom, because at this point in the film, Woodward and Bernstein apparently no longer have time to walk, only run. Poor Sally is forced to clomp-clomp on her high-heeled pumps after him. (As they said of Ginger Rogers, the women had to do everything the men did but backwards and in heels.)

“Do you think he said that to you to impress you, to try to get you to go to bed with him?” Woodward asks her. (Why the hell would that matter?) She stares at him.

“Why did it take you two weeks to tell us this?” Bernstein asks.

“I guess I don’t have the taste for the jugular you guys have,” she says.

Really? This character was based on Marilyn Berger, who would have been 36 when all this went down. With degrees from Cornell and the Columbia School of Journalism, she had already worked as a foreign correspondent for Newsday and went on to report on the national conventions for NBC News.

“She’s an awfully good reporter,” Woodward says to Clawson after Clawson denies her claims. “I don’t remember her getting that much wrong before, do you?”

It’s the nicest thing anyone says about a woman in this movie, but he only says it after implying she’s a whore.

Earlier, before he developed that taste for the jugular, Woodward had used the opposite tactic – backing off and respecting another female Post staffer, thereby inspiring her to use her own allure to get her former fiancé to hand over a list of the members of CREEP.

Whether or not there was sexual interest between them, Berger and Clawson knew each other as former reporters for the Post. The women in this film are depicted primarily as wives and lovers, not a powerhouse among them.

Interesting because guess who was running the Washington Post at the time?

Noticeably absent from the movie is a female who had serious skin in this game: Katharine Graham, owner, president and publisher of the Post throughout the 1970s. Only mention of her in the movie is when Nixon’s Attorney General John Mitchell says in 1972, “Katie Graham’s gonna get her titties caught in the ringer.”

In real life, Graham supported Woodward and Bernstein’s investigative reporting and Bradlee’s decision to give the go-ahead to run their stories, even though the reputation of the paper was on the line. According to a Washington Post story published in 1997, Mitchell’s comment about Graham was “one of the best-known threats in American journalistic history.” The Post published the quote at the time but Bradlee cut the words “her tit.” Graham later said it was “especially strange of him to call me Katie, which no one has ever called me.”

And yet, the filmmakers chose not to depict Katharine Graham in the film during this crucial moment of her reign. She never appears in the movie, except for that mention of “her titties.”

I never noticed any of this in previous watchings of the film. How much did that impact me – these depictions of women (or lack thereof) in the newsroom? Did that impact my decisions as a young reporter, as a young woman trying to launch a journalism career in Washington? That I will never know.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.